Perspective: Carrboro should embrace ADUs as a tool for affordability.

By Michael Melton

Oh, affordable housing. That subject again. Affordable housing is one of the most contentious issues in town, and for good reason. Housing is expensive, and solutions often seem out of reach for the average homeowner. But there is a way for a regular homeowner to help themselves, support a neighbor, and benefit the broader community—all without needing extra land: Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs).

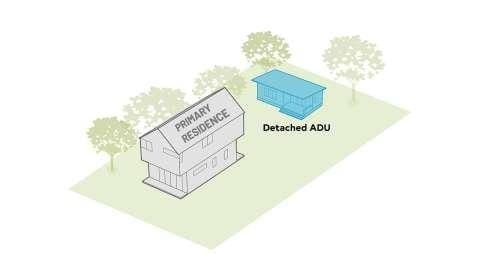

Also called “in-law suites,” ADUs can be attached to the main home, such as a converted basement or garage, or stand alone as a detached unit in the backyard. They provide a secondary living space that can house family members or be rented out at an affordable price. Most detached ADUs range from 300 to 1,000 square feet, offering a practical way to expand housing supply without expanding, redeveloping, or infilling a lot.

Lower Rents, Smaller Footprints

So, do ADUs actually end up being more affordable? Research from multiple cities suggests that ADUs can provide affordable housing options for a range of households. In Seattle, 80% of long-term rental ADUs reported rent at or below the median one-bedroom price in 2022, according to a survey administered by the city. In the Bay Area, roughly half of open-market ADUs were affordable to moderate-income households, and 20–45% were affordable to low-income households, according to the Association of Bay Area Governments. For those units not on the long-term rental market, many were reported as free housing for family members, many for elderly parents.

ADUs are gaining traction in nearby North Carolina cities. Durham recently launched a pilot loan program to help homeowners build or upgrade ADUs for tenants earning 80% of Area Median Income or below, with affordability requirements lasting up to 30 years. In Raleigh, the Fast Track Program offers pre‑approved ADU plans, letting homeowners choose a design that already meets building codes, reducing design costs and speeding up the permitting process.

West End Building Company, a local custom builder, is working to make ADUs more accessible and cost-effective. They are developing a menu of standardized tiny-home designs with set prices, which reduces design costs and speeds construction. Project coordinator Darryl Jones highlighted the Durham Community Land Trust’s tiny-home community, where multiple ADUs on adjacent lots provide affordable housing. He expressed hope that similar projects could appear in Carrboro, dreaming of a tiny development revolution in town.

Stepping Forward

Making Carrboro’s zoning requirements less restrictive could meaningfully expand the number of homeowners who are able to build ADUs. At a recent Town Council work session, members discussed lowering the lot-size requirement from 150% of the minimum lot size to 100%. In simple terms, this means a homeowner would no longer need extra-large lots to qualify—just a lot that meets the standard size for the zoning district. That change alone would immediately make many more properties eligible for ADU permits. Furthermore, Carrboro’s website currently offers no clear guidebook to help residents understand or navigate the ADU process.

Dave Stuckey, a longtime Carrboro resident who lives in Barred Owl, said that making the approval process easier for landowners and contractors, along with offering tax incentives, would encourage property owners like himself to add ADUs. Stuckey also emphasized the importance of living smaller and using land more consciously. After all, why does a family of four need 3,400 square feet? On a two-acre property, a primary residence plus three ADUs could comfortably house ten people.

By easing size requirements, providing user-friendly tools, sharing permitting documents more directly, and forming partnerships with local builders, the Town of Carrboro could better support residents interested in developing ADUs.

Homeowners with the ability to add an ADU should consider it as a way to generate income while helping reduce local rent prices, keeping more money in the pockets of residents and homeowners rather than funneling it to developers.